In my early twenties, I was a self-appointed lothario. Living in New York City, the world was my oyster, there to harvest to my heart’s delight—and so was every woman in it, or so I thought.

I had always surrounded myself with lots of people. Friends, lovers—pawns, as I sometimes considered them.

I was having an affair with my literature professor from college. Unbeknownst to her, I was also messing around with half my softball team, plus assorted others. People I met at bars. Old friends with benefits. An ex I couldn’t quite shake.

I was offending left and right, a far cry from the monogamous relationship this distinguished woman with whom I shared fine meals and road trips and holidays assumed we were sharing. But I kept her isolated from my family and friends, only inviting her in to select groups and moments to stave off the inevitable snark and judgment from others about her age (she was 25 years my senior), and to protect my cheating cover.

It was an April weekend, late morning, the tease of spring in the air but not yet materialized. The city smelled like earth and decay, with a promise of renewed life to come. Off in the distance, the waft of bacon from a breakfast cart hovered on the edge of Prospect Park.

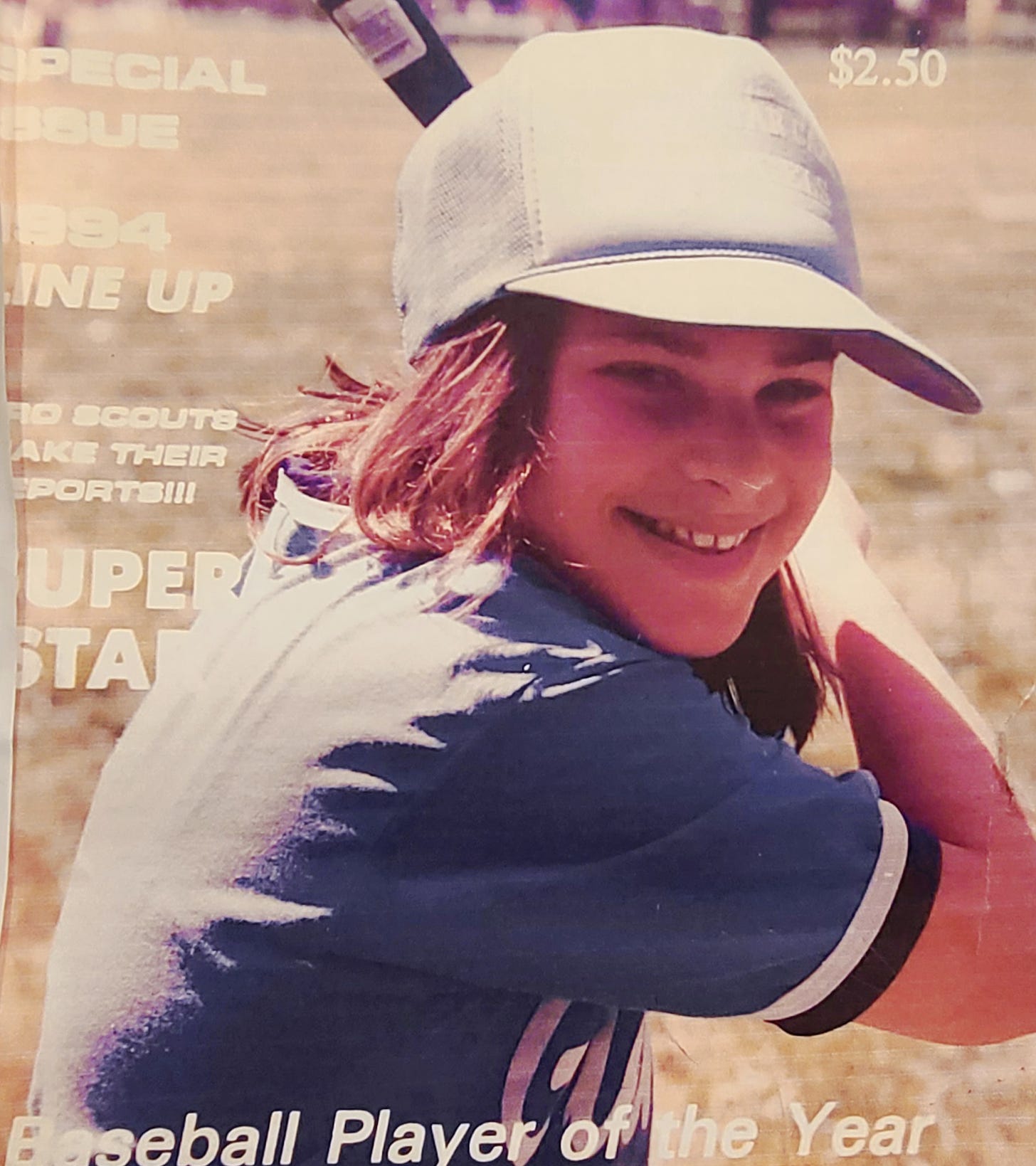

The season opener was within grasp, and we, a dozen odd misshapen lesbians, had taken not to an official sandy diamond for our last softball practice, but a makeshift clearing in the urban woods, replete with bumpy turf outlined by tall, still-bare maples and oaks. The queer softball league always got the last scraps of available space to play.

After practice, we planned to retreat to the neighborhood lesbian watering hole for a team fundraiser. That meant beer and girls and the promise of a night that might create electric memories, one that might not have an ending.

The bulky, masculine, but soft-faced Kristi, our team captain, cracked the bat on the worn softball and we each took our turns fielding the ball, scooping the grounders up in our hide gloves and flipping them to her sidekick, Jamie, an equally broad butch woman with a well-appointed face, who took her after-game beers as seriously as she did her field plays.

Kristi and I had been fooling around. She lived just a few blocks over from the Park Slope apartment where my professor lived. I’d cozy up in her bed after an afternoon of post-game drinking at the bar and then sneak off to the professor’s for the second showing of Masterpiece Theatre and a scotch, neat, followed by a lazy morning after with coffee, black, and traded sections of The New York Times.

Back on the bumpy practice field, it was my turn.

I wiggled my torso, spread my legs, and bent my knees, positioning myself as squarely as possible to center the ball. I heard the crack of the ball against the bat, eyes locked as the spinning white object rolled toward me at a reasonable speed. I got this, I told myself. I pressed the bottom of my glove against the edge of the earth, ready to scoop it up, already practicing the movement of flipping the ball from my glove to my left hand to seamlessly throw it to Jamie and complete the relay.

Well laid plans sometimes go to shit.

Half a second before the ball should have landed in my glove, it hit an uneven path of dirt and hopped up and bit me in the forehead, narrowly escaping my right eye.

The pain wasn’t immediate. The shock hit first. It took me a moment to register what had happened. The sheer force of the hit had knocked me flat on my behind.

I saw my team rushing toward me in slow motion, risti’s mouth agape, her softball jersey flapping.

The shame rushed into my cheeks in hot waves.

“I’m okay,” I said, refusing help as I pushed myself up into standing position.

“We’re not taking any chances,” Jamie said, dialing 911 on her phone.

“That’s really not necessary,” I assured her, but it was too late.

Not 48 hours earlier, Hollywood starling Natasha Richardson had hit her head while skiing and, to the surprise of everyone, dropped dead.

My team, channeling tabloid news, poured their misdirected concern onto me, although their obsessive care was short-lived.

As I sat leaning against a naked, beaten oak waiting for help to arrive, the rest of the team resumed their positions and continued to play.

To make matters worse, the ambulance got lost, unable to navigate city terrain that wasn’t gridded cement. It was a good thing I didn’t really need emergency treatment.

When the ambulance finally arrived, no one from my softball team came with me to the shoddy Methodist hospital in Central Brooklyn. I sat in the ER for hours, alone, watching the most unfortunate cases limping, dragging, and rolling in, hoping I wasn’t dying of a brain bleed and wondering why, with so many people in my life, no one was there with me. I felt like the loneliest social person in the world.

Two hours later, in walked Kristi. Oh good, I thought. Someone from the team was coming to make sure I was okay.

“I’m here to grab your donation for the raffle,” she said. “Do you have it?”

My heart sank as I realized that I was nothing to her, nor to the team. I wasn’t a real friend, just a placeholder on the field so they didn’t have to forfeit. A raffle prize contributor. A warm body to sidle up to in the boozy dark.

It was a sobering moment that would have made my head hurt, had it not already ached from having connected with a hard ball.

It was also not lost on me that I treated others like disposable commodities too, including someone who did care about me.

No sooner did Kristi leave than the professor walked into the ER waiting room. She blanketed me with sympathetic words and tender eyes. She sat with me until my name was called, and a CT scan was run to determine that I didn’t actually have a brain bleed and would live to see the sun set. She smirked through the ER doctor’s flirtatious comments to me that I had “really incredible pupils” while looking into my eyes with a flashlight.

It didn’t occur to me at the time that by refusing to give myself over to someone fully and in earnest, I was missing out on the full experience of human connection. It took a hit to the head for me to truly understand that there was an important distinction between quantity and quality when it came to who I surrounded myself with. More importantly, I realized what type of person I wanted to be to others—and it wasn’t someone who was always on the hunt for the next person to occupy my time.

I never did confess my sins to the professor, but she had a doctorate in decoding subtext. I didn’t have to.

I have just one muse now, my wife of more years than I can easily remember to count. The Brooklyn I romped around in, with its queer subculture and affordable brick row houses, has been replaced with high-priced steel and glass condos and impeccably renovated townhouses. The softball queers have all moved away to the ’burbs to start our own families. The professor married someone more sensible and moved to the Upper West Side.

To this day, when I run my pointer finger across my right eyebrow, I can feel the remnants of the contusion where the ball made impact. If I turn my head at just the right angle in the mirror, I can see the rounded lump protruding out of my forehead.

The only time my softball glove comes out of retirement these days is to play catch with my five-year-old. I have, though, made it a point to teach him how to put his free hand above the glove to prevent the ball from jumping up to bite him in the face. I also taught him that it’s important to treat the people we love with great care. After all, not doing so could come back to bite us in the head, or the heart.

I was not expecting that no one from the softball team would accompany you to the ER! Great essay, I like the way you reveal the lessons learned from this.