After a Splashy Book Deal, I Got Dropped By My Publisher, But I Kept On Writing

Why stubbornness is the most fundamental skill an author can have

This is the thing I’m probably not supposed to write. But I tried to write it six different ways without telling the truth, and I couldn’t do it, so here goes:

My career has not been the success people think it is.

My first book came out from a small press in 2015. The advance was just enough for a fancy steak dinner after taxes. I wrote four more books in that series, and while I was getting some solid acclaim in the crime fiction community, I wasn’t anywhere close to quitting my day job.

And that was fine. I was doing the thing I loved.

Then I wrote a book called The Warehouse, which was pre-empted by a Big Five publisher for a ridiculous amount of money. I thought the book was unpublishable, because it was essentially a fuck-you to Amazon. Then I thought it was would never appeal to foreign markets, but we sold it in twenty languages. It generated enough heat to be optioned for film by an A-list director.

All told, I made enough money off that book to become a full-time writer.

And I thought: This is it, I made it through the door, the rest of my career is going to be sunshine and smooth sailing.

It was not.

The Warehouse got a metric ton of promotion. The cover reveal was in Entertainment Weekly. I did a TV interview on CBS Mornings. It was on every “must read” list going into the August 2019 release. The reviews were glowing.

But it didn’t connect with readers—at least, not on the scale it was expected to. It sold good, but it didn’t sell great. It was supposed to hit the bestseller list and it didn’t, a fact pointed out in one of the major publishing trade magazines. Despite there being a bidding war for the film rights, when the pandemic shut down the movie industry, whatever momentum it had seemed to slam into a brick wall.

For my next book, The Paradox Hotel, my publisher offered me a little less money—still nothing to sneeze at, but a pay cut doesn’t feel good. It’s a mathematically-calculated reminder that you didn’t perform to expectations. Fewer foreign presses bought the rights. The reviews were fantastic, but there were less of them. There was no TV interview.

Again, it sold good, not great.

Hope sprang eternal when a high-profile actress attached to play the lead role in a potential television series. I thought, This is it, this will be my reversal of fortune. A TV show brings with it prestige, and an edition of the book with the actress on the cover, and hopefully, the job security I thought I’d had with the Warehouse deal.

Hollywood being Hollywood, it fell apart. The strike didn’t help.

Things were already looking dire before that happened. Because after Paradox came out, I went through three or four pitches for my next book with my editor, and nothing clicked. Finally, given the lack of an agreed path and my less-than-stellar sales, I was invited to find another publisher.

Essentially, I got dropped.

That’s the thing I’m not supposed to say. Because it conveys weakness. It’s an admission that my sales track isn’t where it should be. That there are cracks in the carefully-constructed facade. I told this tale of woe to writer friends, at conventions and book release parties, and they were shocked.

Optics are funny like that. Everything around the books looked so splashy that success was assumed. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been introduced as an award-winning, bestselling author. Neither of those things were true.

One of the more insidious aspects of social media, at least when it comes to publishing, is the way we only talk about success. The deal memos and the Deadline articles and the unboxings of finished copies. We don’t share the ten or fifteen or twenty failures it took to get us there.

Which is one of the reasons I wanted to write this, because maybe we should talk about those things more.

After I got dropped, I had a real dark night of the soul. I considered quitting—going back to the real world and getting a grown-up job, where I would wear a suit and sit in a box, in exchange for a steady paycheck and employer-funded health insurance. I wouldn’t spill my heart onto a page and then have someone tell me the market wouldn’t bear it.

That lasted about a week.

When I got back to work, it was freeing. I’d gotten stuck in a loop of trying to make a book fit my career trajectory. Something that slotted comfortably next to Warehouse and Paradox. Big idea, speculative, launching torpedoes at rich people and corporations. I was trying to write the thing I thought someone else would want.

This time I figured, fuck it, I’m going to write a book I want to write. That’s why the dedication reads: This one’s for me.

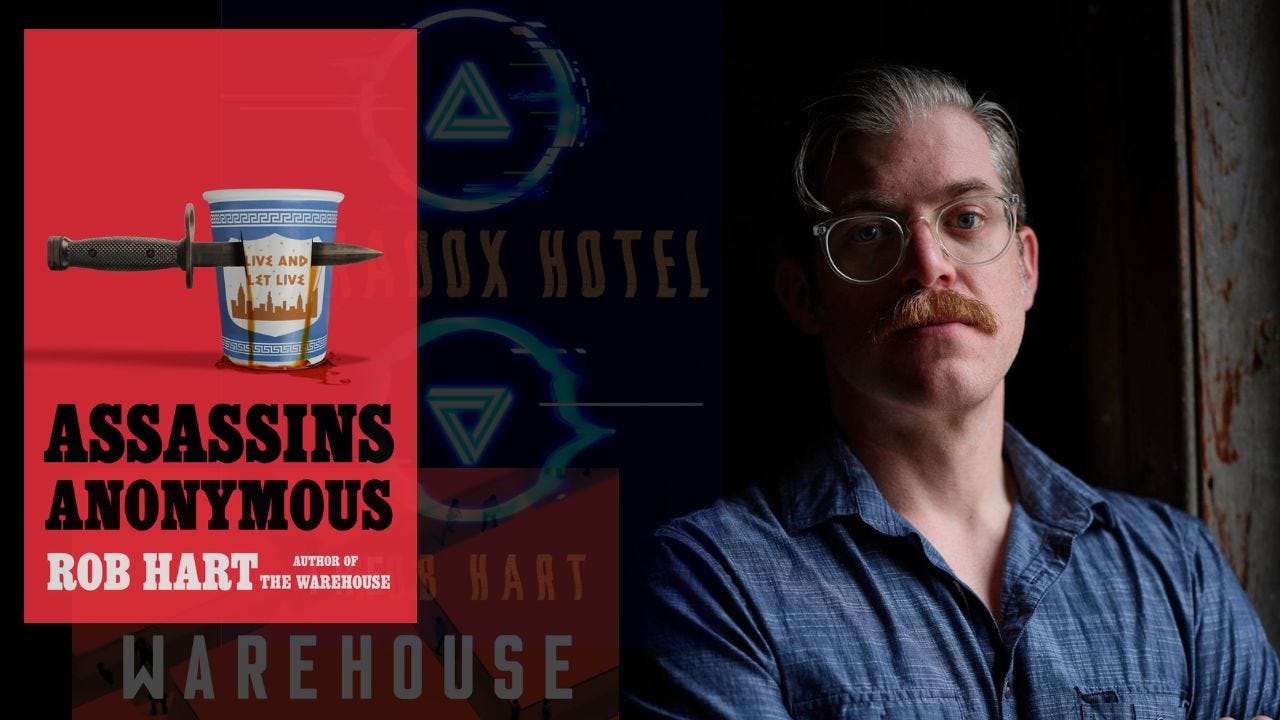

Assassins Anonymous is about a John Wick-level hitman who gets into a 12-step program for killers. I wrote it in five months, the fastest I’ve ever written a book. My agent sent it out and within a week, we were on our way to an auction, and then it was pre-empted.

By my previous publisher.

It was a different imprint, and they had to go to bat to make an argument for why it was worth taking another book from me. It was branded internally as my “pivot” book. The deal was for two books, and it was worth less than what I was paid for Paradox. I’m okay with that. It feels less like a demotion and more like a recalibration, to the kind of advance that’s easier to clear, and doesn’t hang around my neck like an anchor.

It’s still enough to write full-time—though I’m hustling a lot harder for side projects and freelance editorial work. I’d like to not go back to wearing a suit and sitting in a box. If I have to, I will. But I’d rather not.

With a little distance, it’s easier to laugh at all of this. I laughed a lot when it happened, too. It reinforces that publishing is fickle and frustrating. It is not a meritocracy. Eventually art gets overshadowed by commerce. You’re asking a company, with shareholders, to make an investment in you, and if there’s not a return on that investment, well, that’s the way the capitalism cookie crumbles.

But I wrote a book that was good enough for a second chance.

I don’t believe I’ll get a third chance. I’m still wracked with doubt and insecurity. I still lose sleep over the reviews I didn’t get, the lists I didn’t make. Assassins got a nice option too, from another A-list director, but most days I wake up and wonder when my film agent is going to call to let me know the whole thing has fallen apart.

Looking back, I thought a Big Five deal was the top of the mountain. But as 90s Christian nu-metal band P.O.D. sang: the top of every mountain is the bottom of another.

I’m teaching now, too, in an MFA program. Which is great, because I don’t have an MFA myself. It’s a pleasure, working with writers at the start of their careers. When I tell them I’m envious of them, they look at me sideways, but it’s true.

The truth is, I miss those days, when it felt like anything was possible, when the art was all that mattered and I hadn’t experienced the feeling of getting my teeth kicked in by the commerce side.

Yes, we should write for the love of the game, but it’s okay to want the stuff that comes with the major league of publishing: the chance to reach a wide audience, to see something you wrote on a screen, to make a life doing it. To channel all your time and energy into the part of you that wants to share the way you see the world, in all its beauty and tragedy.

When my students ask for the most valuable piece of advice I can impart, I always tell them the same thing: Be stubborn.

Stubbornness is the most fundamental skill you can have in this business.

Maybe there’s better advice, but this is what’s worked for me so far.

Because when Assassins Anonymous came out this past June, it hit the USA TODAY bestseller list. I was at 144 out of 150. It dropped off the list the following week, but at least now, finally, one of the things people assume about me is true.

Rob Hart is the author of Assassins Anonymous, The Paradox Hotel, and The Warehouse, as well as the comic book Blood Oath with Alex Segura and the novella Scott Free with James Patterson. His next book, due in October, is Dark Space, co-written with Segura. Find more at robwhart.com.

I remember reading about The Warehouse and feeling envious. Because I've gotten dropped so many times I wonder if it's brain damage that keeps me writing. I sold my first book to an editor because her sales manager had seen it at another house and had fought for it and lost. But the publisher went out of business six months after my novel was published (and 153 years after its founding). Got a three-book deal with another big NYC publisher that passed on the option for a fourth after seeing three weeks of sales data on the first one; they didn't bother waiting to see how books 2 and 3 did. Published my next four books with a small house just to keep my name in print. Went to the publisher you write about in The Warehouse with a new series, and thought I might finally have found a home. But that publisher, too, passed on the second book in the series three days before the first was nominated for a major award. Five agents have dropped me along the way, too. I've self-published another eight novels, many of which received starred reviews in trade mags like PW. A film/tv creative development group expressed interest in my YA thriller series, but is now ghosting me. Have never quit my day job, but still dream of it. Don't know why I still write, but persistence is why I have 16 novels in print. Tom Clancy once said that writing novels is like digging ditches. It's hard work. But some of us can't not do it.

Dear Rob -- SO PROUD OF YOU, MAN! Thanks for talking about the way things actually work (and don't) in publishing and Hollywood, especially now that publishing is basically Hollywood, Jr. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't, but writing from love is the only things that matters.

And writers -- who ostensibly work to illuminate the true -- need to know the truth about the business they aspire to. The dream is a carrot. The truth is a stick. And the journey is a road that goes on forever, with occasional blinking "Vacancy" signs on the garishly-overlit roadside motels we call "success". Where very few get to stay for long. And most don't last a week.